Revolutionary Aircraft Control System Nears First Flight in Late 2027

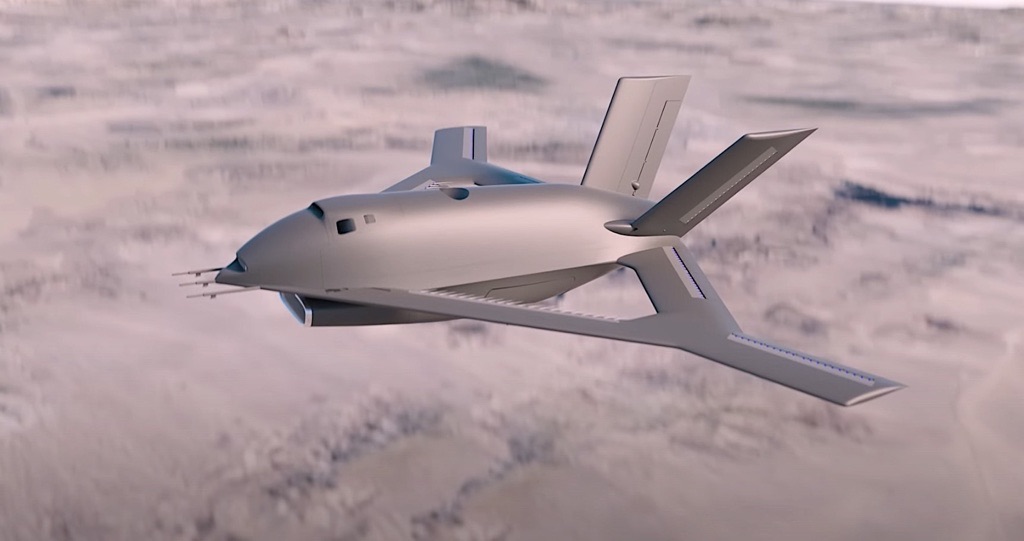

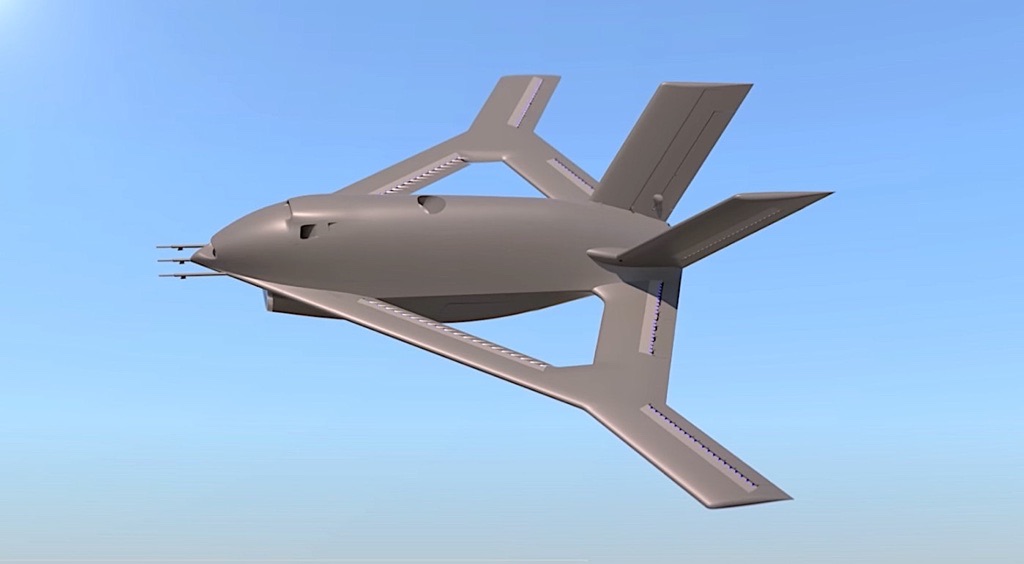

DARPA’s X-65 experimental aircraft is under construction at Aurora Flight Sciences’ Bridgeport, West Virginia, facility, representing a fundamental shift in how aircraft could be controlled. Rather than relying on mechanical flaps, rudders, and ailerons, the unmanned demonstrator will use an Active Flow Control (AFC) system with 14 nozzles that shoot precisely controlled jets of air to manipulate the aircraft’s flight surfaces—essentially replacing physical control surfaces with virtual ones created by airflow manipulation.

The X-65 is part of DARPA’s Control of Revolutionary Aircraft with Novel Effectors (CRANE) program, which aims to prove that eliminating traditional mechanical control surfaces can reduce aircraft weight, complexity, and drag while improving stealth characteristics. The aircraft’s maiden flight is now scheduled for late 2027, delayed from earlier timelines due to technical difficulties encountered during development.

Specifications and Design Philosophy

| Specification | Details |

|---|---|

| Weight | Over 7,000 pounds (3,175 kg) |

| Wingspan | 30 feet (9 meters) |

| Maximum Speed | Mach 0.7 (approximately 537 mph) |

| Configuration | Unmanned, modular design |

| AFC Nozzles | 14 nozzles in wings and tail |

| Wing Design | Low-aspect-ratio diamond shape with straight edges |

| Control Systems | AFC primary + conventional mechanical “training wheels” for safety |

The X-65’s distinctive diamond-shaped wing was specifically chosen as the optimal testbed for the CRANE program. The straight edges and acute sweep angles of this design generate diverse airflow patterns across the aircraft’s surfaces and are inherently susceptible to flow separation—exactly the conditions the AFC system is designed to exploit and control. This unconventional geometry makes the aircraft look like it emerged from science fiction, but every angular feature serves a research purpose.

How Active Flow Control Works

The AFC system fundamentally reimagines aircraft control by using air jets instead of moving surfaces. By selectively activating nozzles on different sections of the aircraft, operators can achieve all traditional flight control functions:

- Roll control: Nozzles on one wing section increase lift, causing the aircraft to bank

- Pitch control: Nozzles at the rear manipulate downwash to adjust nose angle

- Yaw control: Nozzles over vertical surfaces redirect airflow for directional control

- Lift enhancement: Leading-edge nozzles increase lift across the wing

The system offers multiple advantages over conventional control surfaces. Traditional flaps, ailerons, and rudders require complex mechanical systems, control linkages, and structural reinforcement—all adding weight and complexity. The gaps, hinges, and deflecting surfaces of conventional controls also create aerodynamic drag that reduces efficiency. By eliminating these physical surfaces, the X-65 demonstrates how AFC could produce lighter, more efficient aircraft while simultaneously improving stealth characteristics, since there are fewer angular surfaces for radar signals to reflect off.

Safety-First Testing Approach

Despite the advanced AFC system, the X-65 will initially fly with conventional mechanical control surfaces intact. DARPA describes these as “training wheels” that serve dual purposes: they provide a critical safety margin during early flights, and they establish a performance baseline for comparison. As testing progresses, mechanical controls will be selectively locked and replaced until the AFC system demonstrates full control capability across the flight envelope.

The aircraft is designed to reach transonic speeds (near the speed of sound), but the AFC system is also expected to improve performance at lower speeds and high angles of attack—conditions where the diamond wing typically struggles. This comprehensive testing approach will generate data applicable to both military and commercial aviation.

Modular Design Enables Future Research

The X-65’s modular construction allows engineers to swap out wings, AFC effectors, and nozzle configurations without rebuilding the entire aircraft. This flexibility means different AFC designs can be tested throughout the program, and after CRANE concludes, the platform will continue serving as a testbed for subsequent research projects. Aurora Flight Sciences VP Larry Wirsing stated: “The X-65 platform will be an enduring flight test asset, and we’re confident that future aircraft designs and research missions will be able to leverage the underlying technologies and flight test data.”

Comparison with Traditional Aircraft Development

The X-65 differs fundamentally from conventional experimental aircraft like the X-47B or RQ-180 unmanned systems, which still rely on traditional control surfaces. While those platforms advanced autonomous flight and stealth, they didn’t challenge the basic architecture of aircraft control. The X-65 represents a more radical departure—it’s testing whether the fundamental control paradigm itself can be replaced.

In terms of size and speed, the X-65 is comparable to military training jets like the T-38 Talon, which means test data will be directly applicable to real-world aircraft design rather than remaining theoretical. This practical scale distinguishes it from smaller-scale wind tunnels or subscale flight tests.

Timeline and Technical Challenges

The X-65 program has experienced delays—the aircraft is “a few years behind schedule due to technical difficulties,” with the maiden flight now expected in late 2027 rather than the originally planned 2025 timeframe. Construction of the fuselage is currently underway at Aurora’s West Virginia facility, with the distinctive diamond wing awaiting integration.

These delays reflect the genuine technical complexity of developing AFC systems at full scale. While the concept is proven in wind tunnels and small-scale tests, translating it to a 7,000-pound aircraft operating at transonic speeds presents unprecedented engineering challenges in sensor integration, control algorithms, and real-time air jet management.

Broader Implications for Aviation

If successful, AFC technology could fundamentally reshape aircraft design. By eliminating weight and complexity from control surfaces, engineers could reinvest those savings into thinner, longer wings with greater efficiency. The technology could eventually extend beyond flight control surfaces to encompass entire aircraft, potentially creating a “frictionless layer of air” that reduces drag across the entire airframe.

For military applications, the reduced radar signature from eliminating control surface angles offers stealth advantages. For commercial aviation, reduced weight and drag directly translate to fuel efficiency and lower operating costs. For both sectors, simplified mechanical systems mean reduced maintenance requirements and improved reliability.

The X-65 represents a critical inflection point in aviation technology. Its success or failure will determine whether the next generation of aircraft—military, commercial, and everything in between—might operate without the mechanical control surfaces that have defined aviation for over a century. With the first flight now targeted for late 2027, the aviation community will soon have concrete data on whether this radical reimagining of aircraft control actually works at scale.